Andalusia: Photographing Flannery O’Connor’s World

“Where you come from is gone, where you thought you were going to was never there, and where you are is no good unless you can get away from it. Where is there a place for you to be? No place…nothing outside you can give you any place. In yourself right now is all the place you’ve got. ” – “Wise Blood“

My intention was to explore the landscape and Georgia home of Flannery O’Connor to see the settings for her stories. In Spring 2007, when I began the project, more than forty years had passed since her death.

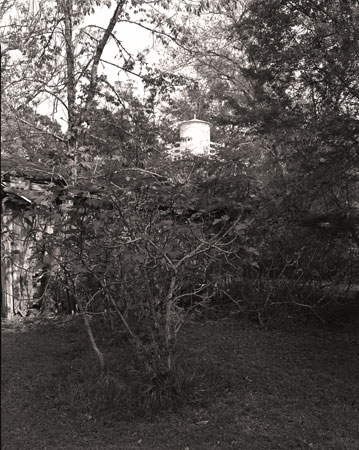

On that first visit, the white iris and wisteria were in bloom. The hinny stood alone under a pecan tree near the old stable to the east of the road. The out buildings were in various states of repair near the main house: a stable, the tenant house known as the “Hill House,” the water tower, the milk processing shed, the calving barn and the big barn. All of these structures figure into the landscape of O’Connor’s stories.

Working with an 8×10 view camera requires moving slowly and looking carefully. Because it is a heavy camera, I had to think about where I put the tripod and then move it myself, since I work alone. The slowness of analog can be an asset when working in an unfamiliar setting.

When I returned home and developed the 13 sheets of films, I was disappointed with the proof prints. This was probably because I needed to make the full effort of making the best print possible using the platinum. Since my best photograph was of Flossie, the hinny, I wasn’t sure if I should go on with the project. Soon after that, I was invited to make an exhibit with an O’Connor symposium at Emory University and was encouraged to go further.

Going back that August, it was very hot, 106 degrees. Too hot for working, but that was my window, so I took precautions against the heat and worked even more slowly. The feeling of summer is in those landscapes. Despite the heat obstacle, this trip produced a few more photographs. There was a still beauty to the place and because of the heat, I had the place to myself.

In winter of 2008 I went back for two more days, so that I could see the farm in clear winter light. The shadows played on form not visible in the atmospheric summer light. The bare tree limbs and winter flowers revealed the bones of this strange and yet familiar landscape.

In Spring 2017 I went back to Andalusia for two days. I wondered if I could add some photographs or if I would see it differently. When I returned to Andalusia, it was a much busier place. Andalusia was on the cusp of being given over to The Georgia College and State University and becoming the Andalusia Institute. There were a lot of visitors in to see the house, so photographing was difficult. I was glad to see that O’Connor’s bedroom/study had hardly changed since I first saw it ten years earlier. Even the mantelpiece was basically the same. There was restoration of the “Hill House” (the tenants house) nearly completed. A peacock shed had been added near the house. I came away grateful that I had photographed there when I did.

Background

The farm itself is 525 acres, so there were many landscapes to look at over the three seasons I photographed there. I am sure that I did not see it all, as visitors were not permitted out of view of the house. I had a little more leeway than most visitors. The big barn was off limits because of safety concerns. I was able to see the hayloft (the setting for (Good Country People) but only from below, as I could not climb the ladder.

Andalusia was called Sorrel Farm when O’Connor’s uncle, Louis Cline bought it in 1947. Sometime later O’Connor learned that the original name was Andalusia. O’Connor insisted to her family that the name be changed back to Andalusia, perhaps to her writer’s ear, a more evocative name than Sorrel Farm.

O’Connor was born in Savannah and lived there during early childhood. The O’Connor family moved to town in Milledgeville where O’Connor attended high school and later the Georgia College for Women, now Georgia College and State University. While she was still in high school, her father died of lupus. O’Connor was accepted to the graduate program of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop at the University of Iowa. She became close to the writers Robert and Sally Fitzgerald who invited her to move to their home in Connecticut where she could have her own apartment and help them with some childcare. During these years after Iowa, she received a residency at Yaddo and spent a brief time in New York City. Sally Fitzgerald later authored “A Habit of Being,” the collection of O’Connor’s letters.

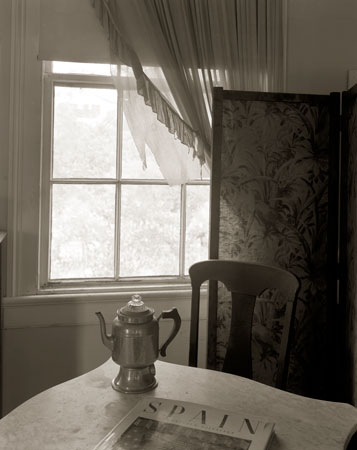

In Connecticut she became very ill and the doctors there diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis but suggested that she go home to Georgia to received medical care. On returning home, she eventually learned that she had lupus. In spite of this debilitating disease, she put a solid three hours in on her writing every morning. Her typewriter was placed on a table near her bed, facing away from the window so that she would not be distracted or walk far. No matter how the illness impacted her, she committed to writing every morning, until her life was ended by lupus in 1964.